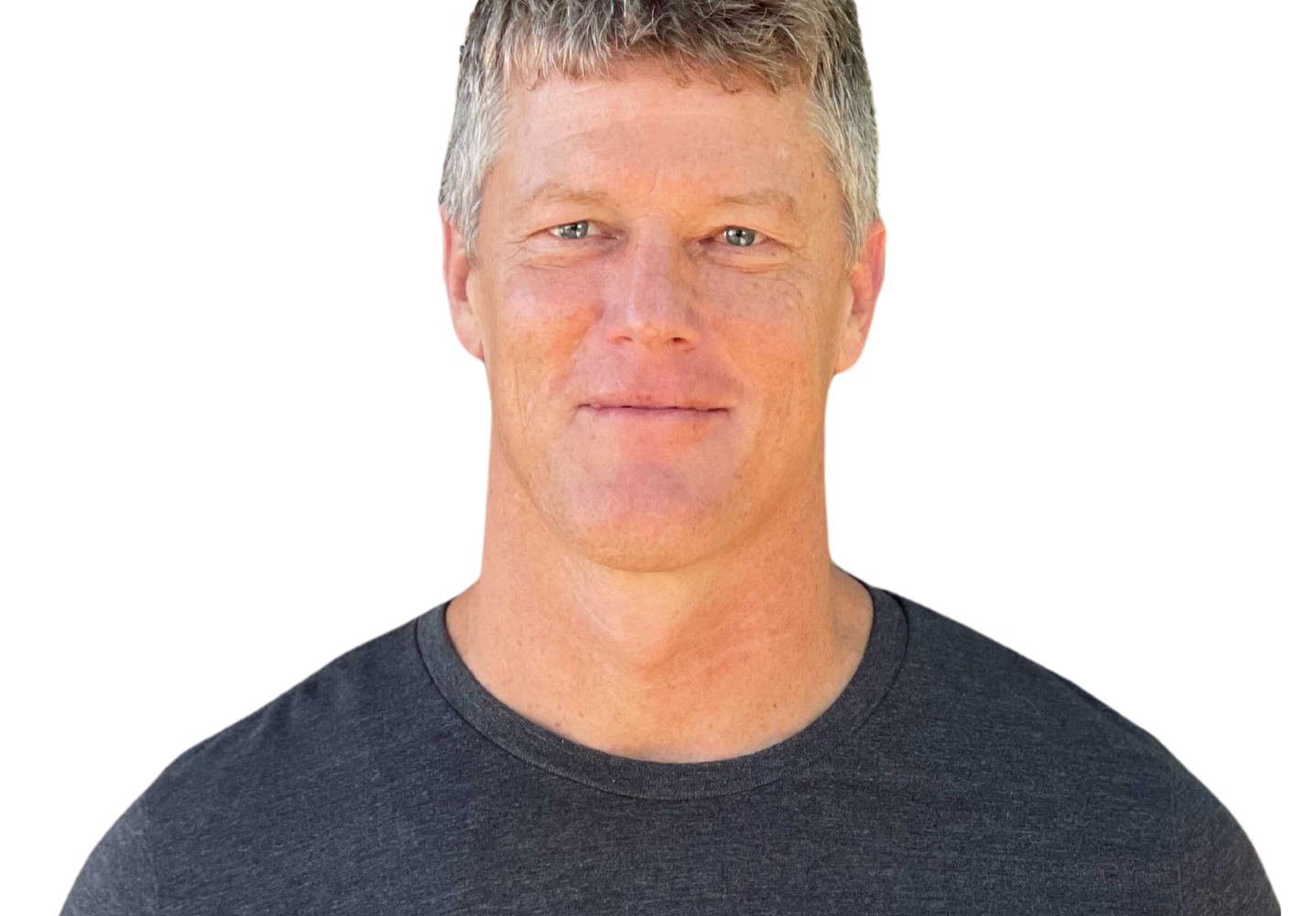

What was the pain point that inspired the creation of Common Room, and why were you the right person to tackle it?

In 2016, I was an investor at Madrona. One of the best things about the opportunity to be a venture investor is that you get to dive deep into industries and business models that are fundamentally reinventing the way software is built, distributed, and adopted. I got to see firsthand the rise of user-led and developer-led adoption within product-led growth, developer services, commercial open source, and the next iteration — web3 and crypto. These early impressions that a seismic shift was happening were validated by my next experience leading product marketing for serverless computing at AWS. There, we found our most innovative services were experiencing gangbusters growth not through a traditional sales-led model but rather through enabling developers to get hands-on with the service, helping them feel supported, and then building and scaling champion programs that would spread education and enablement to more developers. It felt like it should be a win/win for our developers and the business, but I found that the tooling to enable this new engagement model was nonexistent.

A lack of management tooling meant community members often screamed into the void despite our best efforts to keep up. A lack of intelligence and analytics meant identifying the signal from the noise on customer feedback or quickly surfacing customers that needed help was nearly impossible. Don’t even get me started on how we attempted to measure and report on outcomes. In a data-driven growth-oriented organization, a lack of reporting can leave an initiative dead in the water, despite how table stakes it may be. Our developer community was the biggest growth turbine for our business — but we had no way to take action. Many fastest-growing organizations know that partnering with their community is critical to their ability to build better products, have happier users, and grow faster. However, they are stuck in the same situation that I was. I knew this was a problem I wanted to solve.

VC isn’t necessarily a team sport, but when you work with one partner at Madrona, you get access to the power of the entire team … you’re not just partnering with their team, you are then also connected to their entire extended network.

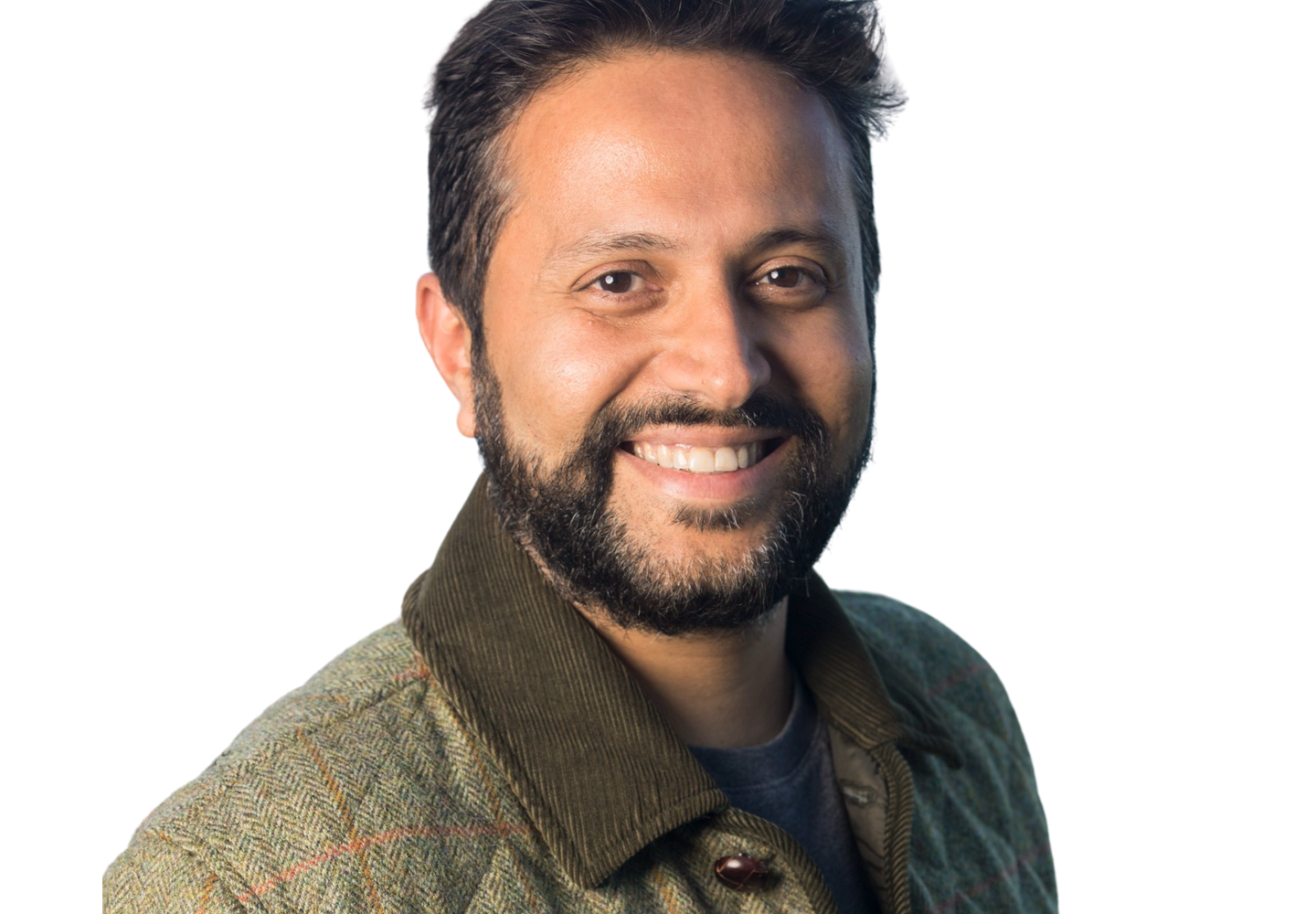

What is it like to work with Madrona?

Being built in Seattle, working closely with Madrona has been incredibly impactful in letting us leverage the rich startup network and ecosystem here. I might be a little biased because I used to work at Madrona. But, for me, what stood out is that Madrona has always been about the people. VC isn’t necessarily a team sport, but when you work with one partner at Madrona, you get access to the power of the entire team — whether that’s any one of the partners, Erika on the PR side of things, Joanna on the legal side, or Shannon on the HR side. Working with Madrona, you’re not just partnering with their team, you are then also connected to their entire extended network. I know if there is anyone I want to meet, particularly in the Seattle area, that person is likely accessible through somebody at Madrona and their network. That is incredibly powerful for new founders.

Tell us about a Madrona Moment.

I talk to Soma regularly — we have a really close relationship, so it’s hard to think of a single moment because he’s been there through so many critical moments. When I was in the early stages of iterating on my idea, Soma often took the time to jam and brainstorm with me. It made me feel like Madrona trusted me to figure out the problem space, understood that I didn’t have it all figured out, and wanted to be a partner in every stage, particularly the beginnings of a company-building process. One of the best things about Soma is that he truly is on the side of the founders. Thinking back, the initial ideation phase of launching a company is a time when founders can feel very vulnerable because we’re trying to figure out what we want to do. And having that non-judgmental thought partner who was on my side and talked through everything with me made such a difference. I trust Soma with any topic, whether it’s the team, the progress of the business, or hiring. When he suggests I talk to someone, I always say yes and get that introduction because he knows me and the company, and I trust his judgment. Soma actually introduced us to our first VP of product, who was a foundational person to get our product up and running in the early days. She’s not at the company anymore, but that was a critical introduction that Soma made. There is truly no single moment with Soma — it is about all the moments.

What have you learned about yourself during this process?

Before I became a founder and CEO, I was always an individual contributor. I had never managed any people. That changed very quickly once we built the company and had a team. So, one of the biggest things I learned is that achievement as an individual contributor is usually about being the smartest person in the room, providing the best input, and trying to do a perfect job on every project. But, once you become a manager, It’s completely different. It’s no longer about being the smartest person in the room. It’s about being a great facilitator. It’s not about always having the most to say. It’s actually about listening. It’s not about perfectionism. It’s about inspiring and leading a team to go and do their best work. That has been a huge seismic mind shift that I’m still on the path of understanding every day.

What is the most important lesson that you have learned during your startup journey?

Building a startup is a roller coaster. You can control so little, so learning ways to keep your baseline steady helps keep you sane. Just look at the last two years with Covid and now the market situation we’re in — these are the global situations we’ve had to navigate as an early startup. And this is just the beginning. Building a startup is kind of like surfing. There are times when you’re paddling. Then you’re waiting for that big wave. It comes, and you’ve got to be ready to catch it. And then, suddenly, you’re waiting for the next wave again. You’re not necessarily in control of when those waves come. In the early days as a founder, you tend not to realize that. You just tell yourself to push as hard as you can for the next three months to hit a certain milestone, but then, right after that, there is another reason you have to push just as hard — and then another three months and another three months and another three months. It is truly a marathon of sprints. There is going to be a lot you can’t control. There are going to be ups and downs. Just accept that, so you can have a more sustainable path and not burn yourself or your team out.